Researchers develop insect counting device for helping with environmental protection

Environment | 02-03-2022 | By Robin Mitchell

Researchers have recently developed an automated method for counting insects in the wild for the purpose of understanding what insects are present, how many there are, and how they are affecting the environment around them. What challenges do insects present, how did the researchers develop an automatic counting system, and how will it help long-term?

Why insects matter, and why they are problematic!

Despite what many may believe, Insects play an essential role in life on Earth. The insect family is unbelievably diverse, with an estimated 10 million different species (currently, 1 million has been catalogued). It is believed that there are 1.4 billion insects for every person on Earth. If all the weight of insects worldwide were added together, it would be 70 times greater than the weight of all the people on Earth.

Insects play a wide range of roles in our ecosystem; some are pollinators that help plants reproduce, some are garbage disposal that decomposes dead animals, and others are predators that feed on other insects, which helps with population control. But human interference in the environment has had a major impact on insect populations, with the honeybee being a famous example. The increasing demand from farmers sees the need to improve crop yields, and this can be done with pesticides that kill plant-eating insects (such as aphids), but this also kills bees who are beneficial to all plant life.

Keeping track of insect populations is essential if one is to understand how the environment is being affected. Still, the only method for doing this involves using traps and manual counting. Not only is this extremely time consuming, but it is also wildly inaccurate as not all insects will be trapped.

Researchers develop automated insect counting system

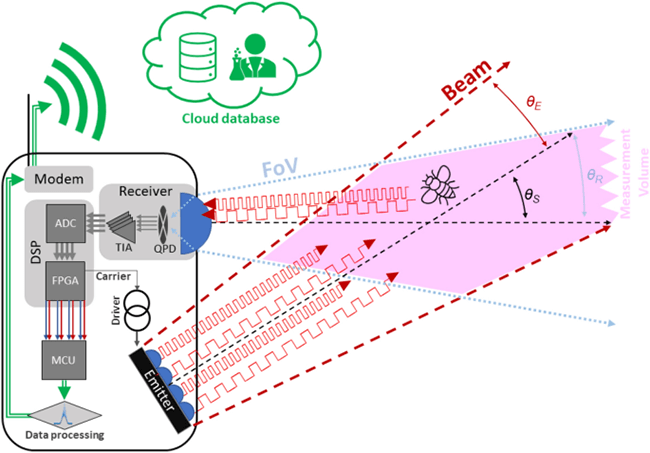

Recognising the need for improved biodiversity tracking, a team of researchers have recently developed a novel approach to automatically detecting the presence of insects as well as cataloguing their type. To detect the presence of insects, the system uses an IR emitter that consists of an array of IR LEDs operating at two different frequencies. This emitted light hits insects which cause IR backscatter, and this reflected light is then detected with a receiver in the kHz sample rate.

However, the receiver is constructed from a quadrant photodiode which allows it to determine the direction of flight, distance, and harmonics in the wing beat.

All of this data is then sent to an FPGA-based DSP that further processes the IR data. This is then sent to a microcontroller for processing and remote transmission via cellular communications. The result is that the device can determine the type of insect (migratory or sensory) and the size of the insect.

Multiple copies of the device were then constructed and placed around a field to monitor the insect activity in a rapeseed oil feed alongside standard yellow water traps (which require manual counting). The result significantly improved accuracy and performance compared to the standard yellow water trap with an estimated 19 times more insect observations with the sensor.

How will this sensor technology help with environmental protection?

One of the significant advantages of the sensor system is that it is fully autonomous and counts every insect that passes its beam, while yellow water traps (yellow buckets with water) only trap insects that fall into them and consequently drown. While insect populations are generally very large, the use of a non-invasive sensor does have the added benefit of helping to reduce the number of insects killed for the simple act of counting.

Of course, the use of cellular sensors allows for these devices to be mounted in any location with cellular access. This can allow researchers to remotely monitor data without being out in the field. However, the ability to receive data in real-time combined with the ability to identify the detected insects could also allow researchers to track insect populations and understand how they move. This could be especially helpful for farmers in areas prone to locust swarms that can devastate entire crops in a matter of hours.