Researchers develop wearable UV sensor by accident

Wearables | 09-03-2022 | By Robin Mitchell

Recently, a team of researchers have developed a wearable UV sensor that can detect damaging amounts of UV, all by accident. What challenges does UV exposure present, what did the researchers develop, and how could passive sensors help human health long-term?

What challenges does UV exposure present?

For those living in the UK, sunlight is something that is never taken for granted, and most will try to get outside on a sunny day. While sunlight is great for BBQs and beach activities, it plays a vital role in human biology, including the production of serotonin and vitamin D. However, too much exposure to sunlight can result in sunburn if the skin is not protected. While sunburns may be a temporary nuisance, they significantly increase the risk of skin cancer.

Sunburns (and the resulting skin cancer) is caused by UV light that makes up a portion of the sun’s spectra. Most of this UV light is absorbed by the atmosphere (thanks to Ozone), but not all of it can be absorbed, and what gets through can quickly damage living tissue.

Protecting against UV light from the sun can be done using proper clothing and taking breaks in the shade, but this is often impractical (especially during a beach day or working outdoors). Unfortunately, the amount of UV light outside and the damage it is causing is invisible to humans as we cannot see the UV spectrum, and the damage from UV only shows up hours later.

For this reason, sunscreen is a vital defence mechanism against UV as it blocks UV from penetrating the skin. But even then, sunscreen wears down over time and must be reapplied, and forgetting to do this can result in skin damage. Overall, UV light from the sun can be considered a silent killer that does not make itself known until it is too late.

Researchers accidentally create a wearable UV detector

Recently, a team of researchers from the Northeastern Kostas Research Institute were working with squid skin to better understand how squids can change the colour of their skin for camouflage. One chemical that is key to squid camouflage is xanthommatin, and the researchers wanted to extract this for study. But once extracted, xanthommatin is unstable and will break down and change colour when exposed to light which caused the researchers extreme difficulty.

However, one of the researchers noticed that the change of colour could be due to UV light, which led to the idea of a wearable device that could detect UV light. With the use of microfluidics, the researchers developed a wearable sensor that impregnates the xanthommatin in a piece of small round paper along with multiple layers of plastic and a reservoir of fluid.

Pushing the sensor causes the fluid in the reservoir to leak into the paper with the xanthommatin, and the pigment changes colour from yellow to red when exposed to too much UV. The device itself is only the size of a fingertip, and the lack of electronics demonstrates how chemical methods can be used for wearable devices.

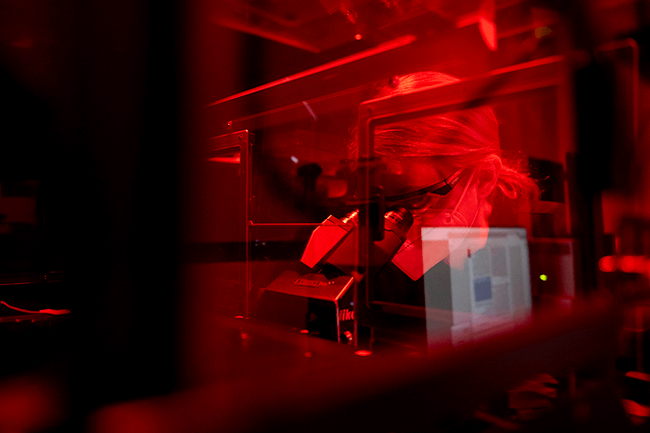

Photo by Alyssa Stone/Northeastern University

How can such devices help prolong human life?

Not all wearable devices have to be electronic in nature, and the development of disposable sensors could play a key role in improving long-term health. That isn’t to say that the sensor developed by the researchers couldn’t be integrated into other wearable technologies to create smart features, but the use of chemical sensors does demonstrate that future wearable devices could be hybrid in nature.

One feature of the wearable UV sensor that was particularly interesting was that the sensor could have sunscreen rubbed over it, which would then inform a user when their sunscreen has stopped working. This could potentially reduce the number of sunburns caused by prolonged exposure, especially in children who are particularly vulnerable to UV light.