Government unplugged over electric vehicles and flat on battery technologies

09-08-2021 | By Paul Whytock

The UK government is nowhere near implementing sufficient electric vehicles (EVs) and related strategies if it intends to meet its much-trumpeted plan to bring the UK’s greenhouse gas emissions to net-zero by 2050.

This forthright statement comes in a report that says actions taken by Government do not coincide with its ambitions to reduce global warming, nor do they take advantage of developmental opportunities in battery and fuel cell technology that this country’s research and manufacturing sectors could provide - opportunities vital to the long-term fight against global warming.

Published by the House of Lords cross-party Science and Technology Select Committee, it brutally clarifies the areas where the UK Government must up its emissions game and lists actions that would assist with that.

Before looking at those, here are some EV facts. Currently, the UK roads have 570,000 plug-in EVs, and the number of public plug-in charging points is around 24,000. So that’s approximately 23 cars sharing one point, although this ratio is much higher in rural areas.

How many charging points does the UK need?

Reports vary but recently, Britain’s competition regulator, the Competition and Markets Authority, said to ensure a robust EV charging network to aid the country’s net-zero plans, it would need 10 times as many before 2030. Other sources have suggested that the UK has introduced on average 7,000 EV charging points annually in recent years, but that rate will need to increase to 35,000 per year.

Taking an international view on this, US Special Presidential Envoy for Climate, John Kerry, has publicly stated that we have less than ten years to implement environmental changes to de-accelerate global warming and that one of those measures is to increase by a factor of 22 the speed with which the world is introducing electric vehicles.

In addition to the deadline on achieving emission targets, a particularly urgent 2027 deadline facing the UK Government and the automotive sector is the Rules of Origin agreement with the EU. This agreement specifies that the battery and 55% of all vehicle’s components are manufactured in the UK or EU. So it’s clear that without the necessary UK supply chains, manufacturing will move to the EU. Related is the 2030 deadline when the sale of new petrol and diesel cars and vans in the UK will cease. Without significant expansion in production capacity, the 2030 target will be undeliverable or will have to be achieved using imported batteries and vehicles.

The House of Lords cross-party Science and Technology, Select Committee report made clear it believes the UK risks losing its existing automotive industry and falling further behind global competitors in battery manufacture. It is also concerned that this country is failing to make the most of its expertise in fuel cells and next-generation battery design.

The Committee was also alarmed by the contrast and apparent disconnect between the optimism of Government ministers about the UK’s prospects and the concerns raised by industry witnesses who fear the UK is lagging behind its competitors and facing significant challenges with innovation, supply networks and skills.

Accordingly, the Committee has called for Government support to develop UK supply networks and secure raw materials for battery manufacture ahead of the 2027 UK-EU Rules of Origin implementation. It also wants actions to ensure the automotive sector has sufficient skilled workers to transition from mechanical to electrical technology.

Looking to the future creation of more ecologically friendly EV related technologies, it also wants increased funding to develop next-generation batteries by the UK. However, during the report’s research, the Committee heard the UK’s current investment in battery research and development is lower and of shorter duration than initiatives in competitor countries.

The Faraday Institution’s current battery research funding is £30 million per year until March 2022. The institute is applying to extend funding and is bidding for an additional £20 million per year to expand its work.

These figures are dwarfed in comparison to the investment plans ratified by the European Commission. Agreed in 2019, the Commission approved €3.2 billion of investments by seven members states to support research and innovation projects in all segments of the battery value chain until 2031. This equates to an approximate average of £270million per year and includes €960million of investments by France and €1.25billion by Germany.

Low public sector funding for UK fuel cell research and development

The Committee also found that public sector funding of fuel cell research and development in the UK is low compared to its international competitors, and financing for fuel cell research has fallen in recent years. It received £8 million in 2021–22 whereas Japan provided around £220 million in 2019 for research and development in hydrogen and fuel cells.

Not surprisingly, because of all this, the Committee is seeking action from Government.

It wants acceleration of the expansion of the public EV charging network to deliver 325,000 points by 2032, including rapid chargers in towns and on the strategic road networks.

It also requests a rapid decision following the consultation on phasing out the sale of new diesel HGVs to spur innovation, and uptake of low-carbon technologies is recommended.

Clarity is also called for via the publication of the Government’s hydrogen strategy and related decarbonisation strategies.

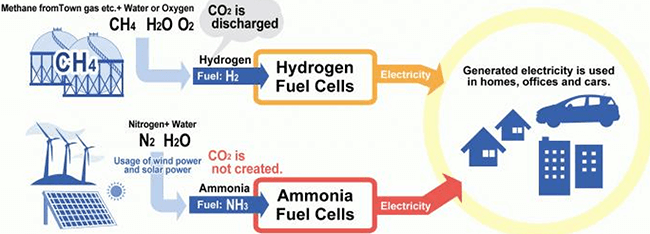

On this last point, hydrogen can be produced in several different ways. The most commonly used method is steam methane reforming which uses heat to break down methane gas into hydrogen and carbon dioxide. However, electrolysis is the most ecologically sympathetic and low-carbon approach, whereby electricity splits water into hydrogen and oxygen. Just one caveat here, though, is the electricity used must be generated from low-carbon sources.

Some fuel cell technologies use other chemicals such as ammonia or methane, but a word of warning is needed regarding ammonia. Ammonia is toxic, and some of its combustion by-products are harmful. It consists of nitrogen and hydrogen, and during combustion, the nitrogen combines with oxygen to produce nitrogen oxide gases. Of these gases, nitric oxide and nitrogen dioxide contribute to air pollution and are detrimental to the ozone layer and nitrous oxide is considered a potent greenhouse gas.

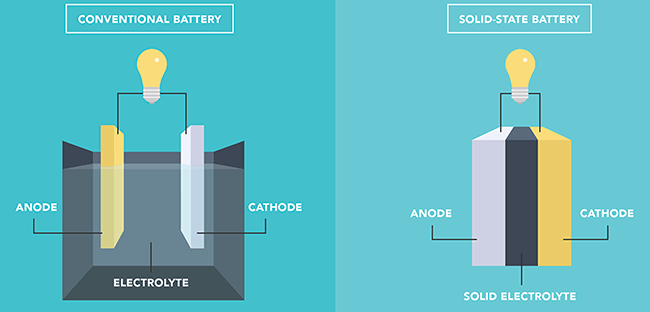

Another area discussed by the report looked at possible next-generation battery designs, and one of these would be solid-state based technology. It felt that some of the challenges in battery performance can be addressed by moving away from liquid electrolytes to a solid-state battery with metal electrodes.

There are four potential advantages of solid-state batteries compared with liquid electrode batteries. These are improved fire safety, higher energy density, faster charging times and longer life.

Due to these advantages, Professor Pasta from the University of Oxford said: “Every automotive company is looking into solid-state, but timescales for development are uncertain, ranging from the 2030s to the 2040s. The Faraday Institution provides £15.3 million over 5 years for the COBALT project that is researching solid-state batteries. This project aims to remove barriers to manufacturing through new materials or processes to enable the commercialisation of solid-state batteries.

One area the report does not comment on, probably because of the seriousness and magnitude of the subject, is how the UK will increase its production of electricity to meet future EV charging demands. Some estimates suggest the supply of electricity in the UK must double at the very least by 2050.

Commenting on the report, Lord Patel, Chair of the Lords Science and Technology Committee, said: “The Committee found the Government’s ambition to reach net-zero emissions is not matched by its actions. The Government must align its actions and rhetoric to take advantage of the great opportunity presented by batteries and fuel cells for UK research and manufacturing.”

“Additionally, the Government must act now to avoid the risk of the UK not only losing its existing automotive industry but also losing the opportunity for global leadership in fuel cells and next-generation batteries. The Government must develop a coherent successor to the industrial strategy and promote its objectives clearly, both domestically and internationally, supported by investments commensurate with those of the UK’s international competitors.”